The benefits of their relationship were very much reciprocal. The fusion of Hindustani classicism with avant-garde jazz seemed natural, but no-one could have anticipated Shankar’s sincere contribution to rock, since it was also at this time that he met his most famous fan and lifelong friend, George Harrison of the Beatles. Saxophonist John Coltrane, for instance, revelled in and grew from Shankar’s training – to the extent that he named his son, Ravi Coltrane, after Shankar. As modal jazz grew, iconic musicians became increasingly captivated with the spiritual framework of the Indian raga.

Backbone of indian classical music free#

He was embraced in the musical metamorphosis of the 1960s, where free improvisation substituted the rules of a rigorous tonal centre. He performed at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, and at Woodstock Festival in 1969. It’s a notion that bodes well for the freedom of expression sought in the West during the 1960s, which Shankar recognised and capitalised on.Īfter completing his sitar training, Shankar toured the world, and found the most receptive audience to be jazz fans, who were excited for a new sound and appreciated complex improvisation. Indian classical music is limitless – it exists to stir emotion.

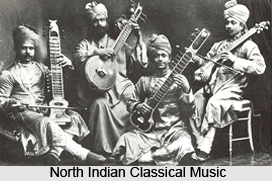

No part of it is confined to the rigorous tonal framework that Western music theory is characterised by rather, flexibility over a metric cycle is encouraged, depending on which mood the performers want to evoke. Indian classical music revolves around a raga, the melodic entity, and a tala, the rhythmic backbone. Shankar, a worldly man at 18, was born in the generation that would define the culture of new India – and he wanted to take it global. The musical connection between the cultures of the hedonistic and consumerist 1930s and Indian spiritualism of antiquity is seemingly non-existent: even at this young age however, Shankar looked like he could bridge this gap.Īs the British Empire weakened during the late 1930s, the idea of a united India was becoming tangible. Shankar left Uday’s tour in 1938 to become Khan’s disciple, where he quickly excelled at the instrument. This heady mix was infused with training from Allauddin Khan, an old master of sitar. His upbringing fostered a cultural open-mindedness that would inform his trajectory as an artist. This Western foray had a profound impact on Shankar, an inquisitive and intelligent teenager who revelled in the Hollywood ‘Golden Age’. At 10, he travelled Europe and the United States as part of a dance troupe led by his brother Uday. Shankar was born in 1920 in Varanasi, the holiest ancient Indian city, to a prosperous but disconnected family. His responsibility for the worldwide dissemination of Hindustani (North Indian) classicism encapsulates the transformative potential of cross-cultural musical blends, if approached with open ears and a curious mind. Rock stars and classical composers – from George Harrison and Jim Morrison to Philip Glass and Yehudi Menuhin – not only admired him but became students, so taken were they with his passion.

Over the course of his life, Shankar rose to international acclaim.

Ten years since his death on 11 th December 2012, his musical ingenuity continues to fascinate audiences. How did the auspicious and evocative sounds of sitar, native to India, become marred with Western pop of the 1960s? We have the legendary virtuoso sitarist Rabindra Shankar Chowdhury, more commonly known as Ravi Shankar, to thank.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)